the below was a project researched and written for an undergraduate seminar on "dead media." i was quite proud of two of the dossiers produced in that class. this was the first.

The Iter Avto

John J. Bovy files a patent for a device in 1921. Bovy describes its aim: “The object is to provide a simple, durable, convenient and efficient device which is adapted to be securely mounted in a convenient place in front of the driver. A further object is to provide means which eliminate the use of large and unwieldy road maps in automobiles when touring throughout comparatively large districts or from State to State” (2). The invention that Bovy describes never reached production. In fact, as we’ll see later, the fate of many conceptual rolling-map devices that defined early automobile navigation would be early death.

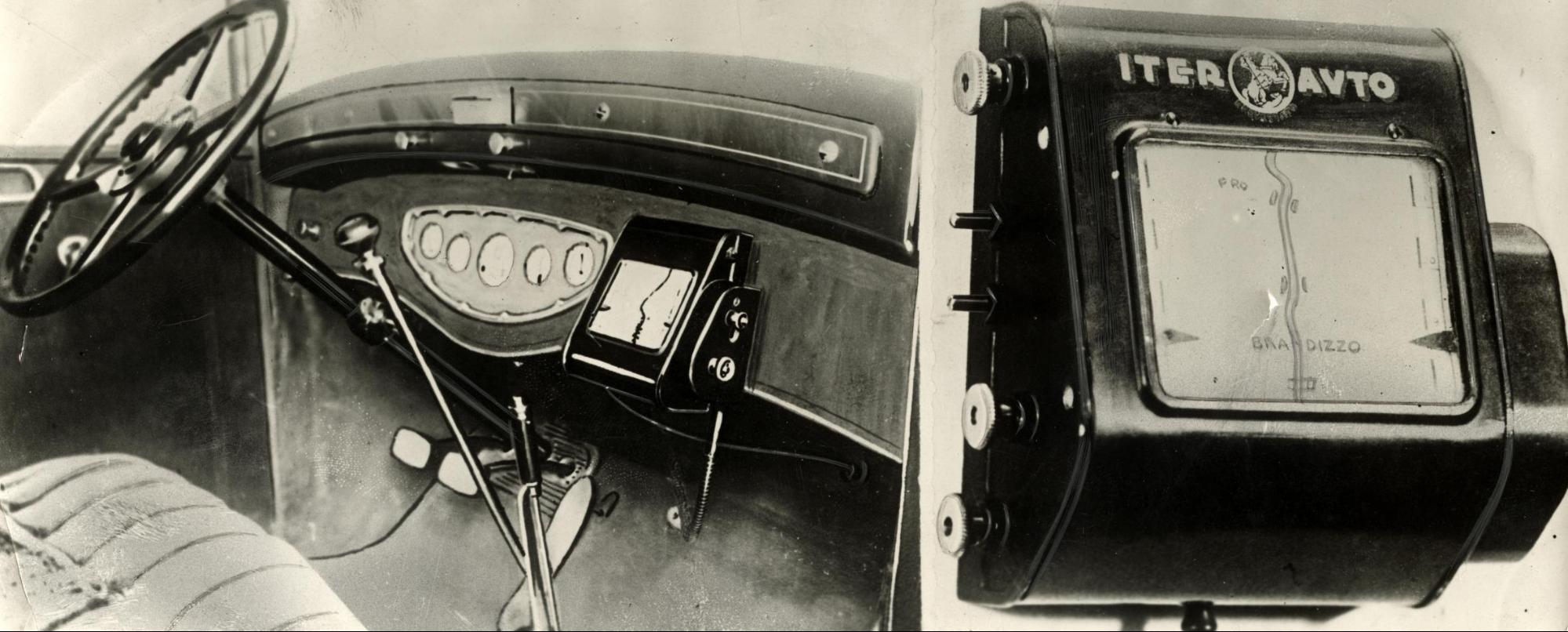

However, the tenants of the patent would eventually be implemented in a device called the “Iver-Avto.” Whether the actual patent was used in conjunction to create the device, or if it was simply parallel thinking that led to the invention closely resembling the fundamentals of the patent, the patent’s descriptions give us insight into how the Iter Avto operated. Bovy’s patent describes a mechanism by which a map printed on a scroll is unwound on one end of the holder and wound by the other. It was not designed for tracking distances or anything quite that sophisticated, instead it was a device meant to hold maps mounted on a steering wheel as opposed to holding a paper map while driving. The Iter Avto was “not quite a decision technology; it was more of a low-level analysis technology. Based on the speed of the car, the system automatically progressed a paper scrolling map display in the direction the vehicle was moving” (Gruber 23). The Iter-Avto builds on the idea of Bovy’s device by being tethered to the speedometer of the vehicle, layering in automation and a completely hands-free opertion that (hypothetically) would be more helpful in determining the driver’s exact location.

“Early Tripmaster Rolling Map.” Nationaal Archief, Museum Syndicate, 1932.

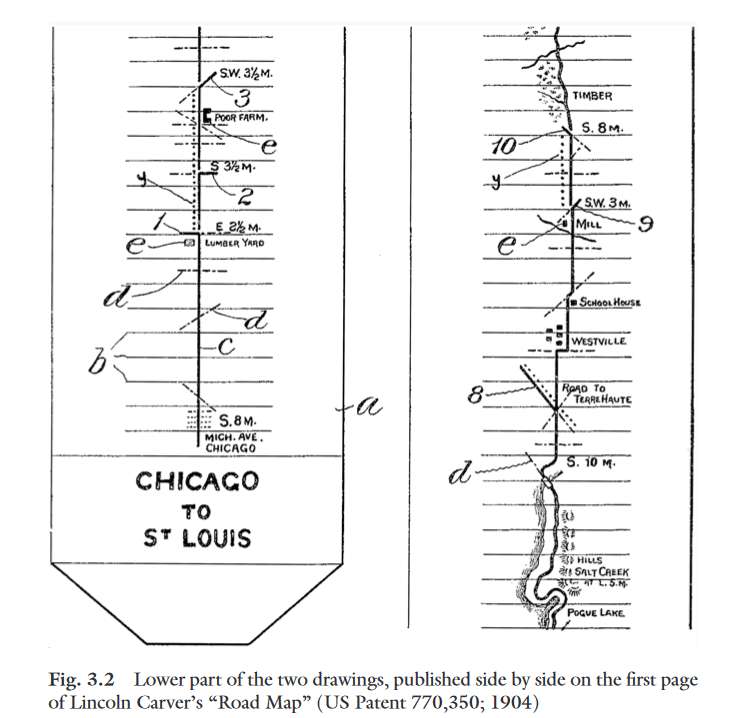

The Iter Avto was part of a larger discourse and imagination that projected maps for automobiles as “strips.” Many assumed that because of the structure of a road, the strip map would work as a way to approximately understand where the driver would be going, in an ongoing straight direction. What was not understood was the growing complexity of the highway system, and the mechanisms were fallible to a degree that made traditional map and landmark-reading far more efficient (Monmonier 65).

From a promotional brochure of the device, the promises made about the product were nothing short of revolutionary: “The Iter-Auto is your Patron Saint on earth who will guide you by the hand in your travels, showing with impeccable accuracy, by means of a route-map turning on in perfect sync with the progress of your car, the way ahead as well as any practical data or information of continuous need.” The advertisement further promises that the driver will no longer need to stop to look at “illegible guideposts” or to check maps.

Some of the major design flaws of the Iter Avto were continual recalibration of maps and replacement of the scrolls, necessitating stoppages.

“ITER AUTO”, Milan Trade Fair, 1932.

The product did not widely penetrate a consumer market.

The Roman Road

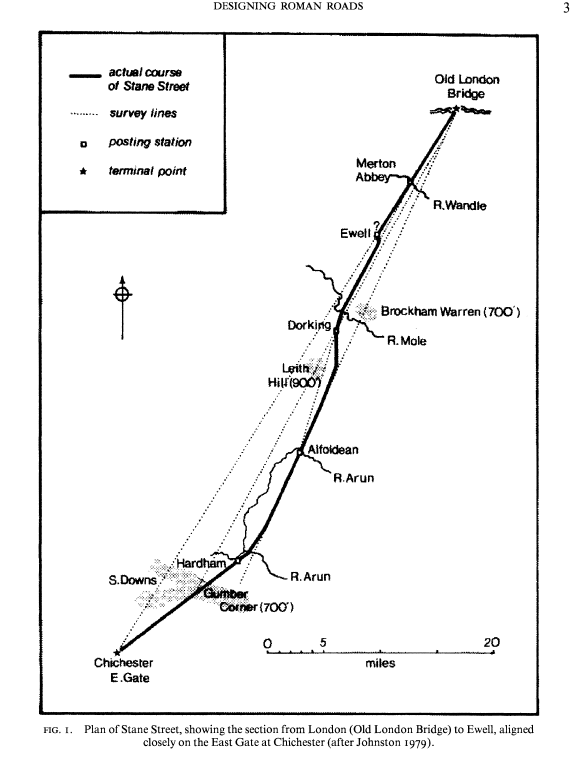

Although the Iter Avto never made a splash and came far too early in the automobile’s lifetime to be considered relevant for most people, we can speculate as to why the device (and other rolling maps like it) did not become the navigational standard. In fact, there may be one pervasive reason that Iter Avto became irrelevant relatively quickly. The Iter Avto was made by an Italian company, and we can see that promotional images for the Iter Avto reference the Italian municipality of Brandizzo. This is important to acknowledge because of the structure of Roman roads, and the differences between it and other, more modern road systems (Rigg).

Hugh E. H. Davies, in Designing Roman Roads, details an explanation of why Roman roads were so straight compared to their modern counterparts: “The likely answer is that the straight sections are not part of the planning process at all, but the outcome of it. It seems inescapable that the required bearing of a proposed road was known in advance to the engineers, so that the road alignment could then be designed to follow this bearing as closely as possible, while also taking account of local geographical features” (2).

“The process starts by identifying the boundary of a region points, being about a third as wide as it is long. Within this region, various identified, inside which roads could be designed. The search gradually narrows, of possible road alignments are available for closer study. Finally a preferred line its position on the ground defined precisely” (5). Davies argues that the reason Roman roads were constructed in such a way that makes for incredibly straight roads with minimal bending was because of the lack of cartographic resources and pressure from the government in order to facilitate the occupation of Britain. This made for an ideal environment, ages later, for navigation via the Iter Avto.

Contemporary Analogues

The Iter Avto is often placed in a historical context through an imagined relationship to GPS navigational technology. However, the fundamentals of each technology are completely different, with a tenuous connection based in a pursuit of automated navigation. It might be more accurate to say that the Iter Avto anticipated a desire for GPS-based devices. The first modern object that seems to resemble a GPS Navigator was the Honda Electro-Gyrocator, that ACTUALLY functioned quite similarly to the Iter Avto. The device would sense mileage and gas-rates, and use that to mark the driver’s location on a physical sheet map that was displayed on a screen. The most fundamental difference in operation was the electronic functions of the Electro-Gyrocator (Arai 2).

“Honda Electro-Gyrocator,” Kotaku, Pedestrian Group, 2 March 2017.

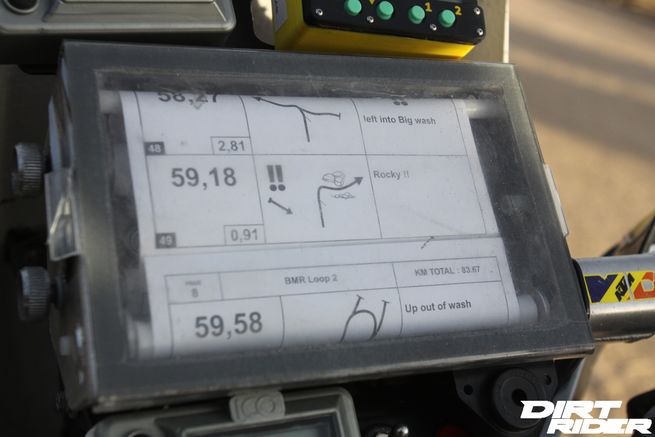

A contemporary equivalent to the Iter Avto are pacenotes/roadbooks for motorbike rallies. The purpose of a roadbook in the rally context is actually fairly close to the experience of automobile navigation in the early 20th century. These devices use a very similar technology to the Iter Avto, and the benefits of the device are the specificity in the small-scale and the ability to mark up portions of the maps (Peterson). Once imagined as a paradigm shift of navigation, the tenants of the Iter Avto lives on in the dashes of motorbikes.

Peterson, Pete. Dirt Rider, Bonnier Corporation, 14 Dec. 2015.

Works Cited

Arai, Masayuki, et al. “History of Development of Map-Based Automotive Navigation System

‘Honda Electro Gyrocator.’” 2015 ICOHTEC/IEEE International History of

High-Technologies and Their Socio-Cultural Contexts Conference (HISTELCON), 2015,

doi:10.1109/histelcon.2015.7307318.

Bovy, John J. Map Holder. 8 Nov. 1921.

Gruber, Dara S. “The Effects of Mid-Range Visual Anthropomorphism on Human Trust and

Performance Using a Navigation-Based Automated Decision Aid.” University of

Minnesota, 2018, pp. 22–25.

Hugh E. H. Davies. “Designing Roman Roads.” Britannia, vol. 29, 1998, pp. 1–16. JSTOR, pp. 1-10. www.jstor.org/stable/526811.

ITER-AUTO. ITER-AUTO. ITER-AUTO, Milan Trade Fair, 1932. Translation by Poemas Del Río Wang, riowang.blogspot.com.

Monmonier, Mark S. Patents and Cartographic Inventions a New Perspective for Map History.

Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 62-75.

Peterson, Pete. “Rally Navigation.” Dirt Rider, Bonnier Corporation, 14 Dec. 2015, www.dirtrider.com/rally-navigation#page-4.

Rigg, Jamie. “The Automated in-Car Navigator That Predated Satellites.” Engadget, 17 Aug. 2018, www.engadget.com/2018/08/03/backlog-pre-gps-navigation/.