This is an abbreviated version of what was meant to be a much longer piece. What follows are the rushed, late-night cobblings of an American working under the anxious delusion that some essayistic keyword accumulation will do anything for anyone.

Here are some organizations taking donations for aid:

Medical Aid for Palestinians Emergency Appeal

Palestinian Children's Relief Fund

In Mark Fisher's blog post What if they had a protest and everyone came?, Fisher, at his most Lyotard, cut down the illusions of the Live 8 charity concert series as nothing more than inane numbing agent for the masses, and elucidates that its status as non-subversive cultural protest lead by wealthy pop stars for a cause designed to provoke/educate imaginary figures such as “the Subject Who Does Not Know (and whose ‘awareness’ is to be raised) and the Subject Who Knows but Who Doesn’t Care” renders it an ideal liberal “Protest.”

It’s possible to see in this writing a reversal (or perhaps reversed application) of the libertarian imagination of “personal responsibility,” specifically for the disconnected Westerner living in the Imperial Core. “But to reclaim that agency means first of all accepting our insertion at the level of desire in the remorseless meat-grinder of Capital. Capital is not something imposed upon us by Bush; it is we who are hooked on the ‘garbage in honey’s sack’, unable to kick the habit of returning to the Big Jesus Trashcan for another hit of feel-good junk.” It’s not that we are being manipulated into the effectiveness of such vacuous moral condescension displays, but it simply feels GOOD to participate in a protest event that is unobjectionable and antiseptic. A positive fulfillment of desires that feeds the rotten state of capital assures us that we will not have to be made to give up any material luxuries or experience discomfort. Theorist Roderic Day goes further, and posits that the notion of wicked puppetmasters who control and manipulate an easily convinced First-World population is specifically an antisemitic one that’s conveniently been able to shake off its Judeophobia webbing.

John Smith’s “Hotel Diaries” are not the witless positivity anthems of Live 8. In fact, they are the symptoms of an energy-drained Western presence witnessing the broken-up spaces he occupies, namely the hotel rooms. In these rooms, he loosely vamps on funny furniture, television, ceilings, hallways, paintings… but his main focus is the devastation of Western imperialism, and its exhausting operations in the Middle East. Lyotard’s libidinal economy sputters with Smith as its agent, as his heavy breathing and clumsy movement operating the camera builds a blockage in the libidinal band; a Plaque, perhaps. In the 5th film of the series, Smith points his camera at the Toblerone bar he’s been eating, which cost a “ridiculous” 5 euros 50, and recounts his pain as he bit into the foil and experienced a nerve shock. The bodily pleasure loop has been exposed raw.

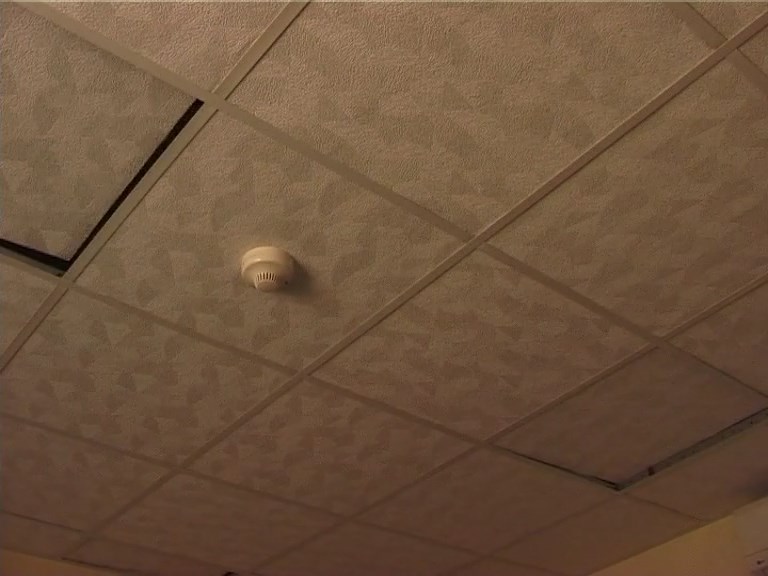

In the 6th film “Dirty Pictures” (in my mind, one of the most vital experimental film works of the digital era), he points his camera at the ceiling of his Bethlehem room, a hotel that was under Israeli requisition until it was re-taken by the Palestinian Authority. The ceiling tiles start jumping, almost playfully, as the wind passes through the space.

It’s an indelible image, and at once humorous and haunted. It’s such classic John Smith that it’s difficult to understand the moment as a spontaneous architectural quirk. It seems almost more possible that this is an elaborate formal scheme from the filmmaker. Smith avoids mawkishness, but compared to his earlier films, this project is practically apoplectic in its political approach. Smith recounts his exit out of the West Bank as he passes through an Israeli checkpoint and witnesses a Palestinian woman who is continuously made to go through a metal detector arch. She wears a surgical boot, and an Israeli commander forces her to take the boot off. She takes the boot off to reveal a stump covered in blood-soaked bandages. After taking off the boot, she walks through the metal detector once again, only to hear it beep again. She is forced towards the other end of the checkpoint, where she walks back to Bethlehem. We stare at John Smith's suitcase and shoes as he tells this story.

It’s an indelible image, and at once humorous and haunted. It’s such classic John Smith that it’s difficult to understand the moment as a spontaneous architectural quirk. It seems almost more possible that this is an elaborate formal scheme from the filmmaker. Smith avoids mawkishness, but compared to his earlier films, this project is practically apoplectic in its political approach. Smith recounts his exit out of the West Bank as he passes through an Israeli checkpoint and witnesses a Palestinian woman who is continuously made to go through a metal detector arch. She wears a surgical boot, and an Israeli commander forces her to take the boot off. She takes the boot off to reveal a stump covered in blood-soaked bandages. After taking off the boot, she walks through the metal detector once again, only to hear it beep again. She is forced towards the other end of the checkpoint, where she walks back to Bethlehem. We stare at John Smith's suitcase and shoes as he tells this story.

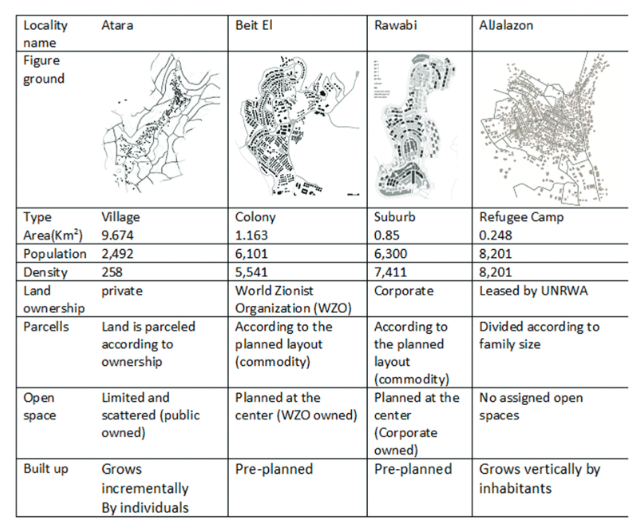

A study of new Palestinian urban morphologies by Professors Salem Thawaba & Hiba Hassoun of Birzeit University (a project I had the privilege of editing in 2022) illustrates how occupation changes the philosophy of urban planning even outside of the immediate construction consequences of the settlements.

‘Atara, an indigenous Palestinian village in the West Bank, is planned as so: divisions of land in ‘Atara followed the property lines, due to the land tenure system. “These lines were irregular, and the size of the plots were determined by Palestinian land ownership and inheritance systems. The plots were demarcated (with title deeds) and the built-up area was integrated into surrounding rural landscapes and green orchards, following an organic layout” (21). The three other case studies embody the consequences of Zionist occupation. The most immediately identifiable is Beit El, a suburban settlement, that forewent the early settler urban planning philosophies of the Kibbutz or Moshave (communal, agriculturally-centered communities) and opted for a new form: the Yishuv Kehillati, which “aimed to fulfill the desire of middle-class families for ‘quality of life’ in ‘gated localities’ while being ‘protected from the undesirables’” (Schwake 241-253).

Past the nakedly racist tenets of the Yishuv Kehillati, we see the Al-Jalazone refugee camp, a chaotic, vertically built community with buildings made of non-durable materials and intertwined roads/architecture. Designed as a temporary solution for those exiled from their homes by Israeli forces, it has become a long-term community for refugees, with urban planning that is ephemeral and rebuilt continuously. Then we have the Rawabi Palestinian suburb, a newer development designed to replicate the settler neighborhoods and by extent destroys the tenets of the indigenous planning philosophy, including the maintenance of organic land flow. The “body” of the land is continuously interrupted by colonial influence.

After witnessing the incident with the injured Palestinian woman forced to walk back to Bethlehem, John Smith ends his anecdote: “The rest of us don’t have much trouble… I didn’t have any trouble at all, as a Westerner. Didn’t even have to open the passport, I just flashed the outside cover and got ushered through. As I walked out into the light outside, along the wall, as you go up the ramp to leave the checkpoint, at regular intervals there are these signs which in three languages say ‘Please Keep the Terminal Clean.’”

Smith shoots video vignettes in his comfortable, anonymous hotel rooms, but occasionally catches something: a frozen television screen announcing US/British bombings in Afghanistan, a view of the wall separating the West Bank and occupied territories, a skunk sticker in the closet (“skunk” was Tony Blair’s nickname, “before he was a war criminal"). Totems of imperial violence are everywhere, and Smith remains occluded in these rooms, insulated from mass terror.

After Smith wonders about the human cost of Western military action in Afghanistan as "payback" for 9/11, he points the camera at a suitcase holder in a corner of the hotel room. Previously having remarked on the uselessness of that piece of furniture, he says "What a waste of time. Haven't you got anything better to do?"